Blog

April 30th is National Golf Teachers Appreciation Day

Southwest Region Championship Results

USGTF Remaining Tournament Schedule For 2014

“Pro” File – Touring Professional Peter Thomson

Social Media Update

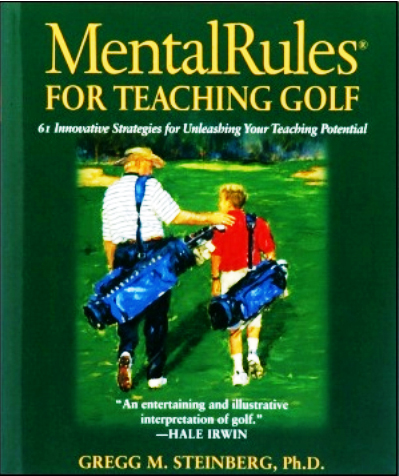

Mental Rules for Teaching Golf on Sale in April; Webinar Still Available

Editorial – Fairway Metal, The Short Game Secret

We have all been there, giving some great insight to a student’s swing fault, knowing they will not practice enough for the changes to become permanent. It is not our place to yell at them and tell them they have to practice to become better. Readmore

Editorial – Get Informed or Risk Getting Left Behind

Back in the 1990s, I authored an article for Golf Teaching Pro about a statistical study in Golf Digest that showed the most important statistic in relation to overall scoring average was greens in regulation. Readmore