Blog

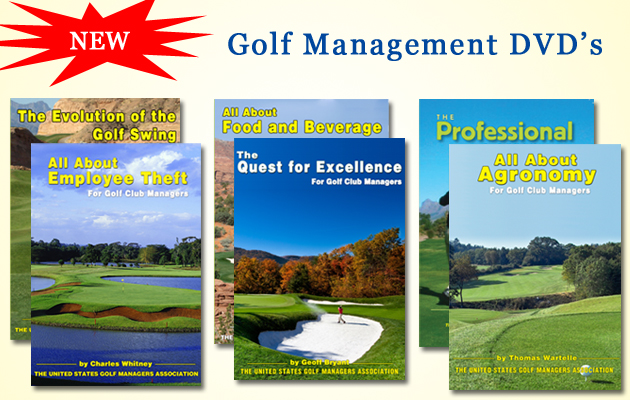

GOLF MANAGEMENT DVD’s AVAILABLE

FIRST BULGARIAN GOLF TEACHERS FEDERATION TOURNAMENT HELD

USGTF-CHINA GOLF TEACHERS CUP HELD IN SHANGHAI

GREAT AMERICAN TOUR PLAYER – WALTER HAGEN

GREAT AMERICAN TEACHING PROFESSIONAL – MICHEAL CARSON

TEACHING ADVICE ON RHYTHM AND TEMPO

TEACHING STUDENT’S ABOUT PATIENCE

USGTF Level IV Member

Port St. Lucie, Florida

Golf is a game of a lifetime…and you as a teacher of this amazing game Readmore

USGTF Level IV Member

Port St. Lucie, Florida

Golf is a game of a lifetime…and you as a teacher of this amazing game Readmore

Do You Have What it Takes to be a Golf Club Manager and Leader?

Teacher Talk

This is not to say a neutral grip is not ideal but is it a prerequisite to play good golf? I don’t believe it is and therefore it should be considered an option in the same way overlap, interlock, ten-finger, double overlap (Jim Furyk), reverse overlap (Steve Jones), intermesh (Greg Norman) and countless other finger formations are chosen by a variety of world class players.

If the orientation of our hands and fingers on the club offer many variations then what should we as instructors be standardizing when teaching an EFFECTIVE grip to our students? Firstly let’s get one thing out of the way. A strong grip does not necessarily cause a hook as a weak grip does not necessarily cause a slice. Could they be contributing factors? Yes of course but three of the aforementioned players above hit fades with a strong grip (Azinger, Couples, Duval). The strong top hand position helped create a “cupped” left wrist at the top of the backswing which opened the clubface just enough in order to hit a fade.

As an instructor it requires experience to take a quick snapshot of a student’s swing and observe how the grip correlates to the clubface position and ball flight. If a slice is the order of the day for your student and weak grip is evident then the correction is evident. The same can be said for a large hook and a strong grip. However if your student hits a power fade with a strong grip, then there is no correction of the grip required. What if he/she hits a big slice with a strong grip and his/her swing is on plane? Believe it or not a weaker grip may be necessary as the strong grip causes too much “cupping” of the left wrist (RH golfer) at the top of the back swing resulting in an open clubface. As one can now understand and appreciate, teaching golf and being good at it isn’t that easy and requires years of experience to hone the craft.

Bottom line there are very few elements to the grip which must be standardized but here they are:

1) The middle joint of the thumbs must be snug to the forefinger otherwise the club may rest too much into the palms. This results into either the club slipping or holding tight so the club does not slip. Proper wrist action is inhibited and tension prevails

2) The heel pad of top hand rests on top of club as shown in image below:

3) The pad of the thumbs should rest on the club slights askew from each other. In other words neither thumb rests on the center of the grip (shaft). For the right handed golfer the left thumb rests toward 1:00 and the right thumb toward 11:00

4) The unification of the hands has nothing to do with interlock, overlap (Vardon grip) etc… What unifies the hands is the top thumb fitting snugly in the lifeline (under the thumb pad) of the bottom hand.

There, that’s it!! The rest is up to you in understanding ball flight and how one’s grip affects the clubface and swing plane.

Next month: What does the tool in your hands do?