Blog

EDITORIAL – Masters History Most Special Among the Four Majors

The Open (formerly called The Open Championship, and prior to that formerly called the British Open) is the oldest of the four majors. The U.S. Open has a storied history almost as long, dating back to 1895. Next up is the PGA Championship, first played in 1916. The Master is the new kid on the block with its debut in 1934, but it can be fairly argued that the history of the Masters is the most special among the four. For one, it is played at the same location every year at perhaps the most famous golf course in the world, with apologies to the Old Course at St. Andrews. Even the most ardent of golf fans will be hard-pressed to describe all the holes on the final nine at the Old Course, but no one has any such trouble with the final nine at Augusta National. Yes, the course is that memorable and special.

The history of the tournament itself is among the most storied. Although none of us were around back then, Gene Sarazen’s double-eagle on #15 during the final round in 1935 is legendary. The 1975 edition featured a battle royal between Jack Nicklaus, Tom Weiskopf and Johnny Miller, and is still talked about to this day.

Nicklaus’ amazing 1986 victory was even better, perhaps matched only by Tiger Woods’ comeback win in 2019. Many observers and so-called “experts” thought Woods would never win another Masters title, as he was too old and could not keep up with the younger generation (as was thought about Nicklaus in ’86). He proved the doubters wrong with a textbook example of course management, attacking at the right time and playing conservatively at others. The roars on #18 after he putted out were said to be the loudest ever heard at Augusta, eclipsing even those of Nicklaus’ 1986 win.

Then there are the details people remember, both successful and not: Curtis Strange dunking two balls on #13 and #15 in 1980, costing him the title; Chip Beck laying up on #13 in 1994 while battling Bernhard Langer; Phil Mickelson pulling off the shot of a lifetime off the pine straw on #13 in 2010; Bubba Watson’s hooked wedge in 2012 during his playoff with Louis Oosthuizen, and many others, too numerous to mention here.

Nicklaus’ six victories leads the way, followed by Woods’ five. Arnold Palmer comes in next with four green jackets. Gary Player owns three of them, as does Sir Nick Faldo, Mickelson, Sam Snead and Jimmy Demaret. No matter which aspect of Masters history we choose to look at, it’s hard to say it’s not the richest in our sport.

By Mark Harman, USGTF Director of Education

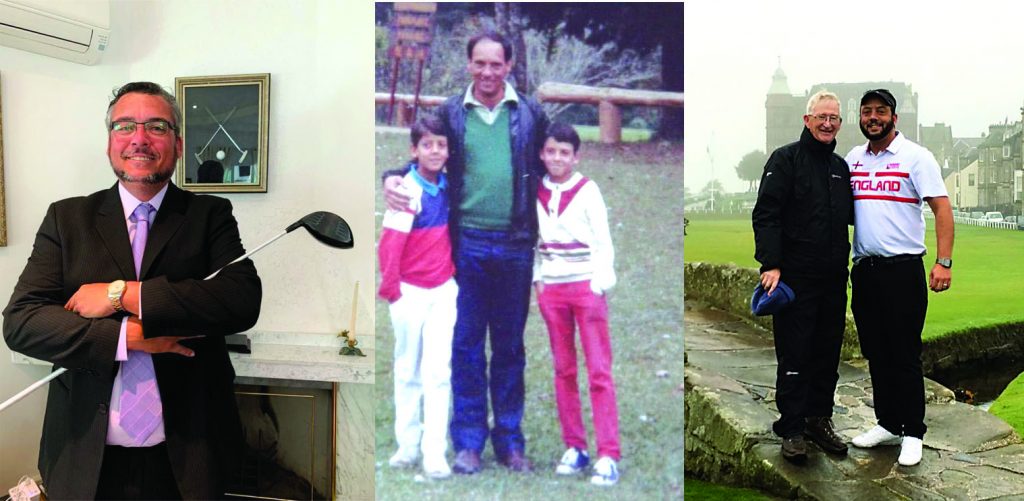

The Correa Family Legacy: Three Generations Of Professional Golfers

WGTF Master Golf Teaching Professional Jack Nicklaus Correa has a strong heritage in the Brazilian golf scene. Both his father Joel Correa and grandfather Guilherme are renowned golf professionals in Brazil; some even say pioneers. They made a career in the golf industry in a country were golf courses were limited and reserved for the wealthy. Like many golf professionals in Brazil, they forged their craft working their way up from the caddie ranks to head professionals. Brazil golf professionals are known for their playing and teaching skills. The Correa family also certainly fits this model. They have competed in tour-level golf, and along the way befriended some of the game’s greats such as Seve Ballesteros, Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer.

Jack Correa was recently elected the president of PGA Brasil. All the members in the room knew of the hard work and dedication to the industry that the Correa family have contributed. There were none more proud than his father Joel. The family has been a steward of the game of golf in Brazil. The torch has been passed to keep the flame alive.

Jack Correa’s brother Kennedy Correa continues the tradition, as well. He continues the legacy in the USA. Kennedy is a golf professional at The Old Course at Broken Sound in Boca Raton, Florida. If you haven’t noticed, Jack was named after Jack Nicklaus and Kennedy was named after John F. Kennedy. Joel and Guilherme’s legacy in the golf industry of Brazil has been passed down to future generations.

Jack Correa’s vision (like his grandfather, father, and brother) is to continue to grow the game of golf. The history of golf in Brazil dates

back to the construction of the São Paulo Railway at the end of the 19th century. Scottish and English railroad engineers constructed and

founded the São Paulo Golf Club.

The Brazilian Golf Confederation, also known as CBG, was created in 1958. This group is similar to the USGA and conducts the amateur events. The Brasil PGA can trace its roots back to the early 1900s, but officially became an entity in 1970. Many dedicated past presidents, such as WGTF members Luis Martins and Luiz Menezes, have helped shape the Brasil PGA through the years of growth. In 2002, Thomas T Wartelle, WGTF Master Golf Teaching Professional and PGA of America member, was invited to Brazil to hold a training course on teaching golf. This, and subsequent training courses, helped further the growth and expand the technical skills of the organization.

After the Olympics in 2016, the growth of the game continues. There are about 25,000 golfers in the country and over 130 golf facilities. In partnership with large companies and sponsors, the federations and golf professionals look to increase the training of young golfers. The

expectation is to reach 250,000 kids through these programs. One such academy is based at the Olympic Club. Correa works with a team

of professionals created to develop a world-class golf training facility. The club features the championship Olympic Course, professional

practice range, short-game area, and a four-hole practice course.

The most famous Brazilian golfer to ever play was Mr. Jaime Gonzalez. His legacy lives on with several PGA Tour players and LPGA Tour players. However, the backbone of golf in Brazil lies in its golf professionals, who work tirelessly to teach and promote the game. Many of the professionals come from families with a strong golf heritage like the Correa family. Often, the profession is passed down several generations. We salute the golf families like the Correas and countless other professionals in Brazil that continue to pursue their passion and grow the great game of golf!

“PGA of Brazil and WGTF partnership has been a tremendous asset to our professionals. Thomas T Wartelle helped develop this relationship between our organizations. His input has been an important partnership to help us reach greater international recognition. The WGTF has furthered our knowledge of teaching techniques. In addition, our relationship keeps us in constant contact with the best teachers in the world and brings that knowledge to share with our Brazilian professionals. We also love the opportunity to share our experiences with other WGTF members worldwide. PGA of Brazil is honored to be in this partnership. We plan to keep working together and look forward to holding more WGTF teaching seminars. This helps us improve our professionals and keeps our relationship growing stronger. We would also like to host the World Golf Teachers Cup at the Olympic Golf Club in Rio de Janeiro one day.”

– Jack Correa

WGTF Master Golf Teaching Professional Jack Nicklaus Correa has a strong heritage in the Brazilian golf scene. Both his father Joel Correa and grandfather Guilherme are renowned golf professionals in Brazil; some even say pioneers. They made a career in the golf industry in a country were golf courses were limited and reserved for the wealthy. Like many golf professionals in Brazil, they forged their craft working their way up from the caddie ranks to head professionals. Brazil golf professionals are known for their playing and teaching skills. The Correa family also certainly fits this model. They have competed in tour-level golf, and along the way befriended some of the game’s greats such as Seve Ballesteros, Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer.

Jack Correa was recently elected the president of PGA Brasil. All the members in the room knew of the hard work and dedication to the industry that the Correa family have contributed. There were none more proud than his father Joel. The family has been a steward of the game of golf in Brazil. The torch has been passed to keep the flame alive.

Jack Correa’s brother Kennedy Correa continues the tradition, as well. He continues the legacy in the USA. Kennedy is a golf professional at The Old Course at Broken Sound in Boca Raton, Florida. If you haven’t noticed, Jack was named after Jack Nicklaus and Kennedy was named after John F. Kennedy. Joel and Guilherme’s legacy in the golf industry of Brazil has been passed down to future generations.

Jack Correa’s vision (like his grandfather, father, and brother) is to continue to grow the game of golf. The history of golf in Brazil dates

back to the construction of the São Paulo Railway at the end of the 19th century. Scottish and English railroad engineers constructed and

founded the São Paulo Golf Club.

The Brazilian Golf Confederation, also known as CBG, was created in 1958. This group is similar to the USGA and conducts the amateur events. The Brasil PGA can trace its roots back to the early 1900s, but officially became an entity in 1970. Many dedicated past presidents, such as WGTF members Luis Martins and Luiz Menezes, have helped shape the Brasil PGA through the years of growth. In 2002, Thomas T Wartelle, WGTF Master Golf Teaching Professional and PGA of America member, was invited to Brazil to hold a training course on teaching golf. This, and subsequent training courses, helped further the growth and expand the technical skills of the organization.

After the Olympics in 2016, the growth of the game continues. There are about 25,000 golfers in the country and over 130 golf facilities. In partnership with large companies and sponsors, the federations and golf professionals look to increase the training of young golfers. The

expectation is to reach 250,000 kids through these programs. One such academy is based at the Olympic Club. Correa works with a team

of professionals created to develop a world-class golf training facility. The club features the championship Olympic Course, professional

practice range, short-game area, and a four-hole practice course.

The most famous Brazilian golfer to ever play was Mr. Jaime Gonzalez. His legacy lives on with several PGA Tour players and LPGA Tour players. However, the backbone of golf in Brazil lies in its golf professionals, who work tirelessly to teach and promote the game. Many of the professionals come from families with a strong golf heritage like the Correa family. Often, the profession is passed down several generations. We salute the golf families like the Correas and countless other professionals in Brazil that continue to pursue their passion and grow the great game of golf!

“PGA of Brazil and WGTF partnership has been a tremendous asset to our professionals. Thomas T Wartelle helped develop this relationship between our organizations. His input has been an important partnership to help us reach greater international recognition. The WGTF has furthered our knowledge of teaching techniques. In addition, our relationship keeps us in constant contact with the best teachers in the world and brings that knowledge to share with our Brazilian professionals. We also love the opportunity to share our experiences with other WGTF members worldwide. PGA of Brazil is honored to be in this partnership. We plan to keep working together and look forward to holding more WGTF teaching seminars. This helps us improve our professionals and keeps our relationship growing stronger. We would also like to host the World Golf Teachers Cup at the Olympic Golf Club in Rio de Janeiro one day.”

– Jack Correa

What Does The Future Hold For The Golf Industry After COVID-19?

It started as a minor news story out of China, and for weeks, it stayed there. Then, reports of the deadly new virus grew ominous with various experts saying the fatality rate of the new virus was over three percent. Early models from Imperial College in the United Kingdom predicted that 2.2 million people would die in the United States if no mitigation procedures were undertaken and 1.1 million would die even if they were.

The COVID-19 coronavirus is not only the biggest story of 2020, it will undoubtedly be one of the biggest stories of the 21st century when the history books are written. The virus has upended daily life all over the planet. It wasn’t long before government officials worldwide began imposing “lockdowns” in an effort to combat the virus. People were ordered to stay home and venture out to only “essential” businesses that provided what were considered the necessities of life, such as food and personal items. Businesses deemed “non-essential” were ordered closed, putting tens of millions of Americans out of work.

Unfortunately, the sport of golf was deemed non-essential by many U.S. governors, and courses by the thousands lay idle. This, despite evidence that being outdoors was one of the best ways to not get the virus. This, despite the fact that the game of golf requires no one to get closer than six feet of another person (one of the mandates of “social distancing”), or that no one had to touch anything that someone else touched. However, other, more enlightened governors realized the benefits of golf and deemed courses essential businesses. These courses were allowed to remain open, with many choosing to alter some aspects. Namely, bunker rakes were removed and pool noodles were inserted in the hole so that retrieving a ball from the hole did not require removal of the flagstick or touching the bottom part of the flagstick in removing the ball from the cup. Water coolers were also taken away.

Many private clubs limited play to members only, with no guests or outside play allowed. Some courses closed their pro shops, taking payment outside and not accepting cash. One-rider-to-a-cart became the norm, and tee times spaced out at 15-minute intervals were implemented at many facilities.

Course dining rooms and clubhouses were closed. With economic damage mounting, states across the U.S. realized that they had to open businesses back up or risk a catastrophe on their hands that would eclipse any of the damage that the virus itself may have imposed – and that point may well have already been passed. Time will tell if the economy will recover or if tens of millions of lives will be destroyed in the sense of mental well being and financial health.

Scientific information is now coming in, showing that not only the shuttering of golf courses was completely unnecessary, but that many of the policies that courses implemented in the name of safety were virtually useless in combating the spread of infection. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently stated that the virus is not easily spread through touch points indoors, much less outdoors. Golf Digest quoted Dr. Charles Prober, professor of immunology and microbiology at Stanford University, as saying, “[Handling the flagstick] is

an extraordinarily ineffective way of getting the disease.” According to Dr. Prober, a series of highly unlikely events would have to occur. First, someone sick with the disease would have to be playing. Second, that person would have to get the virus on their hands through coughing, sneezing, or otherwise transferring body fluids on their hands. Third, they would then have to touch the flagstick soon after.

Fourth, the next person to touch the flagstick would have to touch it in the same exact place as the infected person – assuming the virus was still on the flagstick (more on that later). Fifth, that next person would then have to introduce the virus into themselves by touching their eyes, nose, or mouth within a few minutes of touching the flagstick. In other words, as Dr. Prober pointed out, this highly improbable.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, from Johns Hopkins University, said on golfdigest.com that retrieving a ball from a hole presents “very minimal risks in those types of situations. You can dream up any kind of odd situation where the virus transmits in these special circumstances, but that wouldn’t be something I would be worried about.”

And since Dr. Prober and Dr. Adalja made these statements, new information has come out that the coronavirus doesn’t fare well in sunlight. Willliam Bryan of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said DHS research showed the virus having a half-life of two minutes in sunlight. This means that a maximum of 1/32 of the virus would be left on an outdoor surface after 10 minutes of sunlight

exposure. Therefore, it would seem handling a bunker rake is extremely safe, as well.

Dr. Ezekiel Emanual from the University of Pennsylvania, speaking on the television show Morning Joe, said that in order to get infected, “You need to see a prolonged amount of virus over a period of time. That happens indoors, not outdoors.” He also pointed out that there have been “very few” instances of people getting infected outdoors.

With all of that as the background, the headline of this article asks what’s in store for the future of the golf industry. Right now, signs are highly encouraging. Courses that were under lockdown have seen large waves of golfers. Even courses that were never closed have reported a decent increase in rounds played. Golf retail stores are also seeing business return to near normal, and on many days, exceed their corporate offices’ expectations. That’s not only good news for the retail operations, but also for the club manufacturers and suppliers of these stores.

Demographically, golf is currently faring well. Most golfers have either secure investment income or job security that withstood the economic shutdowns, so the majority of golfers should continue to play. The wild card is how soon the tens of millions of unemployed Americans return to the workforce, as they represent a smaller but significant portion of the golfing population. It would be foolish to venture a guess at this early stage, but hopefully the majority will not be without jobs for long.

The early models reporting that over a million Americans would lose their lives were egregiously wrong, as was the assumption the infection fatality rate was over three percent. While current research from a number of sources, including the Stanford University School of Medicine, the University of Southern California and the University of Bonn in Germany, as well as antibody studies done in Colorado, Massachusetts and New York all show the actual infection fatality rate is likely to be under one-half of one percent, the virus is still a very serious matter. While, as the saying goes, “so far, so good,” the golf industry needs to keep on its toes and continue to promote the game and make people feel confident that they can play without any significant risk.

It started as a minor news story out of China, and for weeks, it stayed there. Then, reports of the deadly new virus grew ominous with various experts saying the fatality rate of the new virus was over three percent. Early models from Imperial College in the United Kingdom predicted that 2.2 million people would die in the United States if no mitigation procedures were undertaken and 1.1 million would die even if they were.

The COVID-19 coronavirus is not only the biggest story of 2020, it will undoubtedly be one of the biggest stories of the 21st century when the history books are written. The virus has upended daily life all over the planet. It wasn’t long before government officials worldwide began imposing “lockdowns” in an effort to combat the virus. People were ordered to stay home and venture out to only “essential” businesses that provided what were considered the necessities of life, such as food and personal items. Businesses deemed “non-essential” were ordered closed, putting tens of millions of Americans out of work.

Unfortunately, the sport of golf was deemed non-essential by many U.S. governors, and courses by the thousands lay idle. This, despite evidence that being outdoors was one of the best ways to not get the virus. This, despite the fact that the game of golf requires no one to get closer than six feet of another person (one of the mandates of “social distancing”), or that no one had to touch anything that someone else touched. However, other, more enlightened governors realized the benefits of golf and deemed courses essential businesses. These courses were allowed to remain open, with many choosing to alter some aspects. Namely, bunker rakes were removed and pool noodles were inserted in the hole so that retrieving a ball from the hole did not require removal of the flagstick or touching the bottom part of the flagstick in removing the ball from the cup. Water coolers were also taken away.

Many private clubs limited play to members only, with no guests or outside play allowed. Some courses closed their pro shops, taking payment outside and not accepting cash. One-rider-to-a-cart became the norm, and tee times spaced out at 15-minute intervals were implemented at many facilities.

Course dining rooms and clubhouses were closed. With economic damage mounting, states across the U.S. realized that they had to open businesses back up or risk a catastrophe on their hands that would eclipse any of the damage that the virus itself may have imposed – and that point may well have already been passed. Time will tell if the economy will recover or if tens of millions of lives will be destroyed in the sense of mental well being and financial health.

Scientific information is now coming in, showing that not only the shuttering of golf courses was completely unnecessary, but that many of the policies that courses implemented in the name of safety were virtually useless in combating the spread of infection. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently stated that the virus is not easily spread through touch points indoors, much less outdoors. Golf Digest quoted Dr. Charles Prober, professor of immunology and microbiology at Stanford University, as saying, “[Handling the flagstick] is

an extraordinarily ineffective way of getting the disease.” According to Dr. Prober, a series of highly unlikely events would have to occur. First, someone sick with the disease would have to be playing. Second, that person would have to get the virus on their hands through coughing, sneezing, or otherwise transferring body fluids on their hands. Third, they would then have to touch the flagstick soon after.

Fourth, the next person to touch the flagstick would have to touch it in the same exact place as the infected person – assuming the virus was still on the flagstick (more on that later). Fifth, that next person would then have to introduce the virus into themselves by touching their eyes, nose, or mouth within a few minutes of touching the flagstick. In other words, as Dr. Prober pointed out, this highly improbable.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, from Johns Hopkins University, said on golfdigest.com that retrieving a ball from a hole presents “very minimal risks in those types of situations. You can dream up any kind of odd situation where the virus transmits in these special circumstances, but that wouldn’t be something I would be worried about.”

And since Dr. Prober and Dr. Adalja made these statements, new information has come out that the coronavirus doesn’t fare well in sunlight. Willliam Bryan of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said DHS research showed the virus having a half-life of two minutes in sunlight. This means that a maximum of 1/32 of the virus would be left on an outdoor surface after 10 minutes of sunlight

exposure. Therefore, it would seem handling a bunker rake is extremely safe, as well.

Dr. Ezekiel Emanual from the University of Pennsylvania, speaking on the television show Morning Joe, said that in order to get infected, “You need to see a prolonged amount of virus over a period of time. That happens indoors, not outdoors.” He also pointed out that there have been “very few” instances of people getting infected outdoors.

With all of that as the background, the headline of this article asks what’s in store for the future of the golf industry. Right now, signs are highly encouraging. Courses that were under lockdown have seen large waves of golfers. Even courses that were never closed have reported a decent increase in rounds played. Golf retail stores are also seeing business return to near normal, and on many days, exceed their corporate offices’ expectations. That’s not only good news for the retail operations, but also for the club manufacturers and suppliers of these stores.

Demographically, golf is currently faring well. Most golfers have either secure investment income or job security that withstood the economic shutdowns, so the majority of golfers should continue to play. The wild card is how soon the tens of millions of unemployed Americans return to the workforce, as they represent a smaller but significant portion of the golfing population. It would be foolish to venture a guess at this early stage, but hopefully the majority will not be without jobs for long.

The early models reporting that over a million Americans would lose their lives were egregiously wrong, as was the assumption the infection fatality rate was over three percent. While current research from a number of sources, including the Stanford University School of Medicine, the University of Southern California and the University of Bonn in Germany, as well as antibody studies done in Colorado, Massachusetts and New York all show the actual infection fatality rate is likely to be under one-half of one percent, the virus is still a very serious matter. While, as the saying goes, “so far, so good,” the golf industry needs to keep on its toes and continue to promote the game and make people feel confident that they can play without any significant risk.

2021 Dues Notices Sent Out – Exciting New Changes

Thank You For The Many Top 100 Teachers Nominations and Support

New Equipment Releases:

International PGA Renewals Now Available at USGTF Headquarters

The International PGA is a strong supporter of the USGTF, the WGTF, and golf professionals everywhere. Certified Golf Teaching Professionals and Master Golf Teaching Professionals in good standing are eligible to become members of the International PGA. To either become a member or renew your current membership, log on to www.InternationalPGA.org or contact the USGTF National Office directly at (772) 88-USGTF ([772] 888-7483).