“PRO” File – Hudson Swafford

It seems the University of Georgia has been nothing short of a professional golfer factory for the past decade, and Hudson Swafford is another in a long line of Bulldog golfers to find success on the PGA Tour. He won the recent Puntacana Resort & Club Championship for his second win on Tour.

Many people think the life of a PGA Tour player is all good all the time, and sometimes it is, but then there is the other side of the coin. Swafford, who previously won in 2017, battled a series of injuries, leading to poor finishes and having to take a medical extension. Although now fully recovered, his mindset wasn’t where it should be until he revealed on Sirius/XM radio that his sports psychologist needled him, saying, “You’re going to lose your card, anyway. You might as well go out and quit worrying about it and have fun playing. You just might get into contention.” Swafford did more than get into contention, assuring himself of a job for the next three seasons.

Customers have called Perfect Practice Putting Mat the gold standard of putting mats, a must have and a go-to rainy-day practice tool, but this product has genuine fans you can look up on YouTube or Instagram. Check out @GolferGirlEm, for example. Among the numerous PGA Tour player endorsements, you will see Charles Howell III, Vijay Singh, Taylor Gooch, Marc Leishman, Lydia Ko, Jimmy Walker and Nelly Korda, along with Dustin Johnson, who is the product’s official endorser and spokesperson.

The original Perfect Practice Putting Mat that has received such acclaim is the 9’ 6” (2.9 m) standard model, but the company has just

released an 8’ (2.44 m) compact and a 15’ 6” (4.72 m) XL version. However, buyer beware…the XL version seems even longer when you are putting to the small hole for a bet. I was really close! It should have gone in, actually, and we never shook hands. You can’t bet real money on an elbow bump.

PuttOUT Pressure Trainer

Customers have called Perfect Practice Putting Mat the gold standard of putting mats, a must have and a go-to rainy-day practice tool, but this product has genuine fans you can look up on YouTube or Instagram. Check out @GolferGirlEm, for example. Among the numerous PGA Tour player endorsements, you will see Charles Howell III, Vijay Singh, Taylor Gooch, Marc Leishman, Lydia Ko, Jimmy Walker and Nelly Korda, along with Dustin Johnson, who is the product’s official endorser and spokesperson.

The original Perfect Practice Putting Mat that has received such acclaim is the 9’ 6” (2.9 m) standard model, but the company has just

released an 8’ (2.44 m) compact and a 15’ 6” (4.72 m) XL version. However, buyer beware…the XL version seems even longer when you are putting to the small hole for a bet. I was really close! It should have gone in, actually, and we never shook hands. You can’t bet real money on an elbow bump.

PuttOUT Pressure Trainer

People like learning through games. Take a difficult task like striking a ball with the equivalent consistency of hitting a bullseye on a dartboard, and you can imagine what the PuttOUT Pressure Trainer is like. One difference is, you can hit a bullseye with a throw that is

excessively hard or easy but arced, whereas you cannot make the ball stay on the ramp of PuttOUT with a putt that is too easy or too hard. very now and again we receive a complaint that the product doesn’t work, which always makes me chuckle and think to myself, “Being good is harder than you think.”

Give a PuttOUT to any young player, and they will become obsessed with mastering it. If you want to teach line and speed, start your layers one foot away and let them take the ten-putt challenge. Allow them to move one foot back each time they can get a ball to stay on the ramp within ten balls. If they can make one ball before their ten run out, they get to move back a foot. This PuttOUT drill is simple, engaging and super fun! PuttOUTs come in a range of colors, great for creating team challenges or stations with easy identifiers.

People like learning through games. Take a difficult task like striking a ball with the equivalent consistency of hitting a bullseye on a dartboard, and you can imagine what the PuttOUT Pressure Trainer is like. One difference is, you can hit a bullseye with a throw that is

excessively hard or easy but arced, whereas you cannot make the ball stay on the ramp of PuttOUT with a putt that is too easy or too hard. very now and again we receive a complaint that the product doesn’t work, which always makes me chuckle and think to myself, “Being good is harder than you think.”

Give a PuttOUT to any young player, and they will become obsessed with mastering it. If you want to teach line and speed, start your layers one foot away and let them take the ten-putt challenge. Allow them to move one foot back each time they can get a ball to stay on the ramp within ten balls. If they can make one ball before their ten run out, they get to move back a foot. This PuttOUT drill is simple, engaging and super fun! PuttOUTs come in a range of colors, great for creating team challenges or stations with easy identifiers.

The company that makes PuttOUT has always had a vision of creating an indoor putting studio. Last year they introduced their ultra smooth PuttOUT Pro putting mat, but new in 2020 are their Putting Gate and PuttOUT Putting Mirror. The company is meticulous about both the design and construction of their products. For example, their mirror features a scratch-resistant coating, a stainless-steel

base so the mirror will not warp, a textured bottom so the product will not slip, and magnetic rails that may be configured for stroke patterns

and drills.

Other products have helped us through the crunch, as well. Nearly every article I seem to make mention of Martin Chuck’s Smart Ball, which is still going strong. We also picked up Jamie Brittain’s Swing Plate, along with the line of Sure-Set products from Dan Frost and Martin Hall, which are all excellent. That said, it has definitely been putting products that have helped us keep the ball rolling so far in 2020.

The company that makes PuttOUT has always had a vision of creating an indoor putting studio. Last year they introduced their ultra smooth PuttOUT Pro putting mat, but new in 2020 are their Putting Gate and PuttOUT Putting Mirror. The company is meticulous about both the design and construction of their products. For example, their mirror features a scratch-resistant coating, a stainless-steel

base so the mirror will not warp, a textured bottom so the product will not slip, and magnetic rails that may be configured for stroke patterns

and drills.

Other products have helped us through the crunch, as well. Nearly every article I seem to make mention of Martin Chuck’s Smart Ball, which is still going strong. We also picked up Jamie Brittain’s Swing Plate, along with the line of Sure-Set products from Dan Frost and Martin Hall, which are all excellent. That said, it has definitely been putting products that have helped us keep the ball rolling so far in 2020.

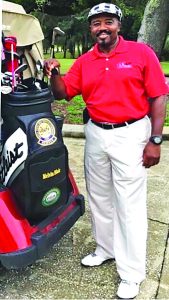

By Melvin Blair USGTF Member Tampa, Florida

Over the years, I invested in the launch monitor FlightScope, and now the Mevo+ is another part of the family. Now, things are better than ever! At BlairsGolf.com, we have the right numbers. The pros only play with the numbers, and you and your students can, as well! Students ask me all the time, “What element of my swing do I need to change?”

My first question is, “How much knowledge or understanding do you have of the ball flight laws?” You would be surprised how many students and coaches say, “Not much,” and that the numbers are confusing. My answer is, “Without the numbers, your golf swing is confusing!”

Something I learned: the ball is an object! It cannot see how pretty your swing looks or how tall you are or how much you weigh or whether you are playing well or poorly. It knows and responds to only one thing – impact, from the moment the clubhead strikes the ball to the moment they separate. The ball collects all the information that it needs to determine which direction, what distance and what trajectory to take. If the golf club strikes the ball with 120 mph of swing speed in the center of the clubface with same loft, clubface angle and swing path, it will go in the same place regardless of who is hitting it.

Ball flight laws are the most important information in which a teacher or student should have at least a reasonable level of knowledge. The knowledge gives us a great understanding of why the ball goes in the direction it is going. Without this knowledge, we can’t give such information as the true angle of attack, clubhead speed, club path, face angle, face-to-path or smash factor. I tell students, if you notice your golf ball when it is in the air for a long time with your slice, there is a good chance your spin is high. If your golf ball lacks rollout and seems to stop immediately when it lands, you are probably playing with high spin. If it seems like the ball lands softly and reacts immediately when it hits, there is a strong indication that you have high spin. And understanding how spin works and where your spin needs to be is the first step in fixing your slice, which is the evil of golf!

Golf instructors now know the important relationships between two critical things – the clubface angle and the club swing path. They know this is the key to understanding the slice. This can be done only with a launch monitor, because your eyes are not that good!

Club Data

• Club Speed

• Attack Angle

• Club Path

• Swing Plane

• Swing Direction

• Dynamic Loft

• Spin Loft

• Face Angle

• Face-to-Path

Ball Data

• Ball Speed

• Launch Angle

• Launch Direction

• Spin Axis

• Spin Rate

• Smash Factor

• Height

• Carry

Coach Melvin Blair is the golf coach for BlairsGolf.com, is a coach for the First Tee of Tampa Bay, ran the Disabled Veterans Golf Association, Inc., passed the V1/PGA Education Teaching and Technology advanced course, and is a member of the USGTF. Blair credits the USGTF for changing his golf life and giving him the tools he needed to teach and play golf at a high level.

By Melvin Blair USGTF Member Tampa, Florida

Over the years, I invested in the launch monitor FlightScope, and now the Mevo+ is another part of the family. Now, things are better than ever! At BlairsGolf.com, we have the right numbers. The pros only play with the numbers, and you and your students can, as well! Students ask me all the time, “What element of my swing do I need to change?”

My first question is, “How much knowledge or understanding do you have of the ball flight laws?” You would be surprised how many students and coaches say, “Not much,” and that the numbers are confusing. My answer is, “Without the numbers, your golf swing is confusing!”

Something I learned: the ball is an object! It cannot see how pretty your swing looks or how tall you are or how much you weigh or whether you are playing well or poorly. It knows and responds to only one thing – impact, from the moment the clubhead strikes the ball to the moment they separate. The ball collects all the information that it needs to determine which direction, what distance and what trajectory to take. If the golf club strikes the ball with 120 mph of swing speed in the center of the clubface with same loft, clubface angle and swing path, it will go in the same place regardless of who is hitting it.

Ball flight laws are the most important information in which a teacher or student should have at least a reasonable level of knowledge. The knowledge gives us a great understanding of why the ball goes in the direction it is going. Without this knowledge, we can’t give such information as the true angle of attack, clubhead speed, club path, face angle, face-to-path or smash factor. I tell students, if you notice your golf ball when it is in the air for a long time with your slice, there is a good chance your spin is high. If your golf ball lacks rollout and seems to stop immediately when it lands, you are probably playing with high spin. If it seems like the ball lands softly and reacts immediately when it hits, there is a strong indication that you have high spin. And understanding how spin works and where your spin needs to be is the first step in fixing your slice, which is the evil of golf!

Golf instructors now know the important relationships between two critical things – the clubface angle and the club swing path. They know this is the key to understanding the slice. This can be done only with a launch monitor, because your eyes are not that good!

Club Data

• Club Speed

• Attack Angle

• Club Path

• Swing Plane

• Swing Direction

• Dynamic Loft

• Spin Loft

• Face Angle

• Face-to-Path

Ball Data

• Ball Speed

• Launch Angle

• Launch Direction

• Spin Axis

• Spin Rate

• Smash Factor

• Height

• Carry

Coach Melvin Blair is the golf coach for BlairsGolf.com, is a coach for the First Tee of Tampa Bay, ran the Disabled Veterans Golf Association, Inc., passed the V1/PGA Education Teaching and Technology advanced course, and is a member of the USGTF. Blair credits the USGTF for changing his golf life and giving him the tools he needed to teach and play golf at a high level.