Blog

USGTF Tournament Update

USGTF Online Courses Finding Value with New Members

New Era of Golf Technology on Display

Rudy Project and USGTF Continue to Partner

Golf Is An Essential Business

“Pro” File – Touring Professional Tim O’Neal

Editorial: Pro Golf Returns!

What’s Important In Teaching Juniors

Passing down the great game of golf to younger generations has many rewards and provides a unique gratification. The strength and duration of the game also relies on it. We have an obligation to teach our love of the game to the youth of the world, and you never know when you may be the fuel that ignites a junior golfer into having a chance for a better education through attaining a college scholarship, or even a career in the game.

For teaching juniors, we have to look at the unique requirements and guidelines that their age and development dictate. Because of this, I have separated juniors into two age groups:

1) Elementary school age: The surest way to turn a junior in this age group away from golf is to get into technique. While fundamentals need

to be learned, the priority is fun. The kids must find enjoyment in the game. A few thoughts here to accomplish this:

Teach in groups. Kids at this age are used to learning in groups. Keep the activities fast-moving and interesting. Splitting up into pairs for fun competition works great for this age. Your goal should be to teach the fundamentals with short, easy visual cues and phrases that are blended into activities. Another way to think about this is to teach the kids things like alignment, grip, rules and etiquette, without them realizing that is what they are learning. A common misstep is to teach segmented lessons, as you would an adult.

I would also urge an instructor to make two things a cornerstone of any program. The first is to utilize other sports into the program. For example, combine golf exercises like making a putt with kicking a soccer ball or tossing a ball to a target. The second would be to utilize the junior aids and golf-specific learning tools that can be found easily online. Some of these aids are extremely popular and a big hit, not just with the kids but also with the parents, because it shows thought and effort went into the teaching.

The last point with this group is equipment. I cannot stress enough the importance of proper length and weight clubs. Improper equipment

can ruin the initial golf experience for juniors as well as cause motor skill pattern issues that will be discouraging and difficult to overcome, and is a major factor in kids not taking to the game.

• Fun • Competition • Partners •

• Integrate other sports • Age specific aids •

• Appropriate clubs •

2) Middle school age: For starters, with this age, group teaching is much less effective. Keep presentations to a minimum and do not expect

to hold their attention for longer than a couple of minutes. Remember, this is the smartphone generation. Technique also becomes much more important because these kids are stronger and what they learn, conceptually and physically, will determine whether they stay in the game or give it up.

At this age, the importance of the short game should be emphasized. The instructor should work all parts of the game. Use groups for quick points, but keep things moving as fast as possible. Get into a one-on-one teaching situation quickly. Good putters are born at an early stage of golf learning. Putting setup and stroke fundamentals provide an easy opportunity for improvement. Chipping is incredibly important at this age because it can rescue them from bad shots and keep the score down when they play, which is critical to keep them engaged in the game.

Kids at this age will rebel against “little kid” games, so focus on finding ways to teach technique without becoming too rigid. They are listening; they just do not want you to know it. For a retention check, challenge them to teach back to you what they have learned. In contrast, set up drills that create a challenge and at the same time teach technique.

At this age, it is very important to find interesting ways to teach the kids how to practice. This is a skill that they can carry through their hole life as a golfer. I highly recommend using the basic practice sequence of Block-Variable-Test. This also keeps them moving and challenges them. The instructor should not be timid in terms of challenging them slightly. They view that challenge as your recognizing them as older and more mature. Be positive always, but blend in constructive points for improvement and set up tests to gauge their learning progress and retention.

When teaching the swing, focus on balance, stability, and sequence. You can also introduce the concepts of face, path and low point, but keep it simple. When they hit bad shots, instead of patronizing, challenge them to explain what happened and always make them feel involved in the learning process as well not being overly directed. The quicker they learn the basic concepts and understand their own swings,

the more likely they will enjoy improving and practicing. The one big advantage for teenagers is the ability to adjust motor skill patterns more

easily than adults. Therefore, the instructor should not hesitate to make swing adjustments.

Lastly, teenagers want two things in their instructor: credibility and a sense that you are genuinely interested in helping them. Credibility

comes with demonstration as well as explaining the why’s. If they understand why they need to do something, they will buy in. Genuine care

and concern should come out in the way you interact with them and the genuine enthusiasm you display. If they feel you are not genuine or are going through the motions, they will shut off.

• Individual instruction when possible •

• Very short presentations • Teach practice •

• Teach swing technique • Teach short game •

• Be genuine •

Passing down the great game of golf to younger generations has many rewards and provides a unique gratification. The strength and duration of the game also relies on it. We have an obligation to teach our love of the game to the youth of the world, and you never know when you may be the fuel that ignites a junior golfer into having a chance for a better education through attaining a college scholarship, or even a career in the game.

For teaching juniors, we have to look at the unique requirements and guidelines that their age and development dictate. Because of this, I have separated juniors into two age groups:

1) Elementary school age: The surest way to turn a junior in this age group away from golf is to get into technique. While fundamentals need

to be learned, the priority is fun. The kids must find enjoyment in the game. A few thoughts here to accomplish this:

Teach in groups. Kids at this age are used to learning in groups. Keep the activities fast-moving and interesting. Splitting up into pairs for fun competition works great for this age. Your goal should be to teach the fundamentals with short, easy visual cues and phrases that are blended into activities. Another way to think about this is to teach the kids things like alignment, grip, rules and etiquette, without them realizing that is what they are learning. A common misstep is to teach segmented lessons, as you would an adult.

I would also urge an instructor to make two things a cornerstone of any program. The first is to utilize other sports into the program. For example, combine golf exercises like making a putt with kicking a soccer ball or tossing a ball to a target. The second would be to utilize the junior aids and golf-specific learning tools that can be found easily online. Some of these aids are extremely popular and a big hit, not just with the kids but also with the parents, because it shows thought and effort went into the teaching.

The last point with this group is equipment. I cannot stress enough the importance of proper length and weight clubs. Improper equipment

can ruin the initial golf experience for juniors as well as cause motor skill pattern issues that will be discouraging and difficult to overcome, and is a major factor in kids not taking to the game.

• Fun • Competition • Partners •

• Integrate other sports • Age specific aids •

• Appropriate clubs •

2) Middle school age: For starters, with this age, group teaching is much less effective. Keep presentations to a minimum and do not expect

to hold their attention for longer than a couple of minutes. Remember, this is the smartphone generation. Technique also becomes much more important because these kids are stronger and what they learn, conceptually and physically, will determine whether they stay in the game or give it up.

At this age, the importance of the short game should be emphasized. The instructor should work all parts of the game. Use groups for quick points, but keep things moving as fast as possible. Get into a one-on-one teaching situation quickly. Good putters are born at an early stage of golf learning. Putting setup and stroke fundamentals provide an easy opportunity for improvement. Chipping is incredibly important at this age because it can rescue them from bad shots and keep the score down when they play, which is critical to keep them engaged in the game.

Kids at this age will rebel against “little kid” games, so focus on finding ways to teach technique without becoming too rigid. They are listening; they just do not want you to know it. For a retention check, challenge them to teach back to you what they have learned. In contrast, set up drills that create a challenge and at the same time teach technique.

At this age, it is very important to find interesting ways to teach the kids how to practice. This is a skill that they can carry through their hole life as a golfer. I highly recommend using the basic practice sequence of Block-Variable-Test. This also keeps them moving and challenges them. The instructor should not be timid in terms of challenging them slightly. They view that challenge as your recognizing them as older and more mature. Be positive always, but blend in constructive points for improvement and set up tests to gauge their learning progress and retention.

When teaching the swing, focus on balance, stability, and sequence. You can also introduce the concepts of face, path and low point, but keep it simple. When they hit bad shots, instead of patronizing, challenge them to explain what happened and always make them feel involved in the learning process as well not being overly directed. The quicker they learn the basic concepts and understand their own swings,

the more likely they will enjoy improving and practicing. The one big advantage for teenagers is the ability to adjust motor skill patterns more

easily than adults. Therefore, the instructor should not hesitate to make swing adjustments.

Lastly, teenagers want two things in their instructor: credibility and a sense that you are genuinely interested in helping them. Credibility

comes with demonstration as well as explaining the why’s. If they understand why they need to do something, they will buy in. Genuine care

and concern should come out in the way you interact with them and the genuine enthusiasm you display. If they feel you are not genuine or are going through the motions, they will shut off.

• Individual instruction when possible •

• Very short presentations • Teach practice •

• Teach swing technique • Teach short game •

• Be genuine •

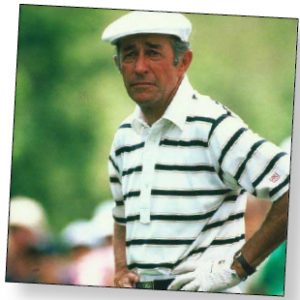

Thoughts From Toski

USGTF Member, Boca Raton, Florida

I have been asked to write this article at the request of Bob Wyatt, who was in my junior class at my first club job at Kings Bay in Miami, Florida, in 1957, after I retired from the tour.I have read the series of articles in your magazine and must compliment those instructors who have passed on their knowledge of the golf swing and golf in general. In observing the modern golf swings today, I have noticed the following techniques:

I have been asked to write this article at the request of Bob Wyatt, who was in my junior class at my first club job at Kings Bay in Miami, Florida, in 1957, after I retired from the tour.I have read the series of articles in your magazine and must compliment those instructors who have passed on their knowledge of the golf swing and golf in general. In observing the modern golf swings today, I have noticed the following techniques: