The Y Solution

The Y Solution is a new term that I have invented to explain the confluence of three branches as represented by the letter Y: spatial awareness, coherence, and proprioception. Each branch has a unique influence on the game of golf.

Before we begin, let’s define each branch so we can better apply teaching our clients.

SPATIAL AWARENESS is the ability to be aware of oneself in space. It is an organized knowledge of objects in relation to oneself in that given space. Spatial awareness also involves understanding the relationship of these objects when there is a change of position.

PROPRIOCEPTION is the sense of the orientation and relative position of neighboring parts of the body and the strength of effort being employed in movement. The ability to swing a golf club or to catch a ball requires a finely tuned sense of the position of the joints. Proprioception is a ten-dollar word to describe your awareness of how your body is moving based on how the muscles feel.

COHERENCE is an optimal physiological state where your heart, mind and emotions are harmoniously functioning in alignment and cooperation. In my opinion, it is the main branch of the letter Y that supports the other two components.

Now that we have defined the three branches, let’s apply the Y Solution to the game of golf.

Research shows that when we activate the state of coherence, our physiological systems function more efficiently. We experience greater emotional stability, and we also have increased mental clarity and improved cognitive functions. Simply stated, when our mind and emotions, brain and body work in harmony with our heart, we feel better. We care more, and our performance lifts us at work and in our interactions.

We all want players to get their focus and concentration on the target rather than swing thoughts. Spatial awareness, which requires keeping your eyes on the ball when your target is hundreds of yards in the distance, demands the ability to create a clear mental picture. Only then can you make a truly target-oriented swing that has been freed up.

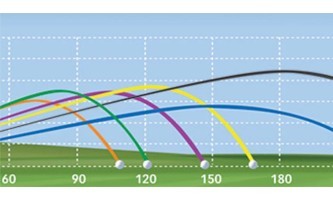

It boils down to this: What a golfer should be seeking to produce is a reflex response to visual, auditory and kinesthetic stimuli (sight, sound and feel). Your brain must operate from the subconscious. Before settling over the ball, you must build a complete picture of your target, including the flagstick, landing area, trajectory and roll. Loading the wrong software is done by picturing a bad shot.

The best way to enhance proprioception is through targeted exercises and golf drills. It is vital that we as golf instructors identify exercises and golf drills that are player-specific to the issues that we want to work on. For example, we want to improve overall hip rotation to enhance proper slotting in the plane to avoid the over-the-top swing fault. When the player understands and feels the relationship of where the body must be in relationship to the club, we will see proprioception at work.

Next time you see your client holding a golf club at the setup position, think of the Y Solution.